15+ Years of FIRST Robotics: What Corporate Tech Can Learn from High School Teams

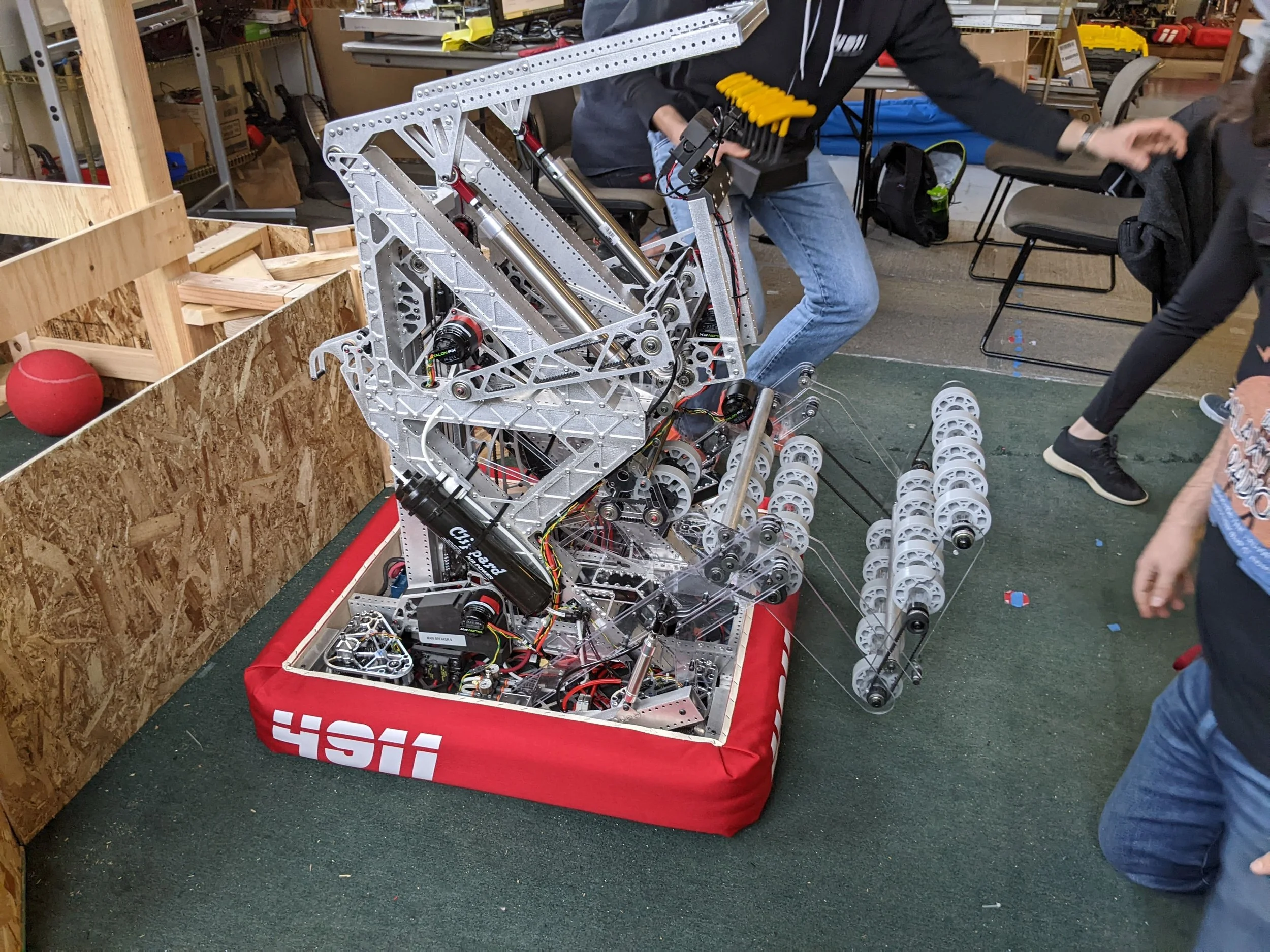

A photo of FRC 4911’s 2022 robot.

I know what you're thinking: "What could a bunch of high schoolers possibly teach seasoned engineers at Google, Microsoft, or Tesla?"

Trust me, I had the same skeptical mindset when I first got dragged—practically kicking and screaming—into FIRST Robotics by a persistent teacher over 15 years ago. (Yes, that makes me feel ancient, thanks for asking.) What started as reluctant participation became a passion that's shaped not just my career, but my entire perspective on what great engineering teams actually look like.

Here's my journey in a nutshell: student → volunteer → mentor → corporate software engineer at IBM and Boeing → still mentoring FRC Team 2910 "Jack in the Bot" today. I've spent years watching the tech industry celebrate how much students learn from their industry mentors, but we're missing the bigger conversation entirely.

What can corporate tech learn from these scrappy high school teams?

After watching billion-dollar companies struggle with problems that 16-year-olds solve daily, I've got some thoughts.

1. Mentorship Doesn't Require a Senior Title (Or Any Title at All)

Walk into any thriving FIRST team's workspace, and you'll see something beautiful: a sophomore teaching a senior how to CAD a gear train. A junior explaining programming concepts to a mentor. A freshman who's been tinkering with electronics since age 10 showing everyone how to troubleshoot a sensor issue.

No org charts. No "you need five years of experience before you can teach." No gatekeeping. Just knowledge flowing freely in every direction.

Now think about your last corporate job. How many brilliant junior engineers sat silently in meetings because they didn't feel "senior enough" to contribute? How many good ideas never surfaced because someone with a "Software Engineer I" title assumed their perspective didn't matter?

I've watched high school students teach me things that fundamentally changed how I approach problems. At Boeing, some of my best insights came from our newest team members—the ones who hadn't yet learned what was "impossible."

The magic happens when you create an environment where anyone can teach and everyone can learn. Your newest intern might have the fresh perspective that unlocks your most challenging technical problem. But only if you've built a culture that values insight over tenure.

2. The Game Changes Every Year (And That's the Whole Point)

Every January, FIRST releases a new game with completely different rules, scoring mechanisms, and strategic challenges. Last year's robot? Completely useless. Your perfect strategy from 2023? Irrelevant. The game manual might as well be written in hieroglyphics because nobody—not the veteran mentors, not the championship teams, not anyone—has seen this challenge before.

And you know what happens? Magic.

Suddenly, the mentor with 20 years of engineering experience is learning alongside the freshman who just joined the team. The playing field levels. Everyone's a beginner again, and everyone's input becomes valuable because nobody has "the answer."

Compare this to corporate tech, where I've watched senior engineers coast on knowledge they gained five years ago, resistant to new frameworks, new languages, new approaches. "We've always done it this way" becomes the death knell of innovation.

The best FIRST teams embrace this annual reset. They know that their willingness to learn, adapt, and iterate is what separates them from teams that get stuck trying to rebuild last year's winning robot.

When was the last time your company voluntarily threw out everything they knew and started learning from scratch? When did your team last approach a problem with genuine curiosity instead of assumptions based on past solutions?

The most successful teams—whether they're building robots or building software—stay humble enough to admit they don't have all the answers. They stay curious enough to keep looking for better ones.

3. Your Real Competition Isn't Other Companies

Here's something that blew my mind during my corporate years: watching companies obsess over what their competitors were doing instead of focusing on what they could become.

I've seen this pattern everywhere. IBM had Watson making headlines, then seemed to pause and admire their own innovation while Google, OpenAI, and others sprint past them in the AI race. Intel dominated processors for decades, then got comfortable—now they're scrambling to catch up with AMD and ARM.

Meanwhile, the top FIRST teams I've worked with barely mention other teams unless they're sharing strategies or celebrating each other's innovations. Their focus is relentless: How do we build a better robot than we built yesterday?

Team 254, "The Cheesy Poofs," is legendary in FIRST not because they spent years studying their competition, but because they spent years pushing the boundaries of what they thought was possible. They compete against their own potential, and the championships follow naturally.

The corporate equivalent would be companies that focus on solving harder problems, building better products, and serving users more effectively—not companies that spend board meetings analyzing competitor pricing strategies and market positioning.

Your competition isn't the company across the street. Your competition is complacency. Your competition is the voice that says "good enough." Your competition is yesterday's version of yourself.

4. Every Solution Is a Trade-Off (And Students Get This Better Than Most Engineers)

Ask any veteran FIRST team about their robot design, and they'll give you a masterclass in systems thinking:

"We could make the arm faster, but that would require a bigger motor, which would add weight, which would slow down our drivetrain, which would hurt us in the autonomous phase. Instead, we optimized for consistent scoring over raw speed because our analysis showed..."

These kids intuitively understand that engineering is about intentional compromises, not perfect solutions. They weigh trade-offs constantly: speed vs. reliability, complexity vs. maintainability, innovation vs. risk.

Now walk into most corporate engineering meetings. How often do you hear conversations about trade-offs? How often do engineers present multiple viable approaches with honest assessments of the downsides?

Too often, I've seen teams present one solution as "the solution" without acknowledging what they're giving up to get there. Or worse, they spend months chasing a perfect solution that doesn't exist, paralyzed by the fear of making the wrong choice.

FIRST teams don't have that luxury. Build season is six weeks. Ship date is non-negotiable. They learn to make informed decisions quickly, live with the consequences, and iterate in the next version.

The best engineering happens when you stop looking for perfect solutions and start optimizing for the right trade-offs. High school students building robots understand this. Why don't we?

5. Success Isn't Just About Winning

Here's the thing about FIRST that took me years to fully understand: the teams that build sustainable, long-term excellence aren't the ones obsessing over trophies. They're the ones building confidence, celebrating growth, and redefining what success looks like.

I've mentored teams that never won a regional championship but produced students who went on to transform entire industries. I've seen teams celebrate a first-time successful autonomous routine with the same joy others reserve for major victories. I've watched students develop unshakeable confidence not because they won everything, but because they learned to take pride in progress.

Corporate tech could learn from this mindset. How many companies abandon promising projects because they didn't immediately capture market dominance? How many engineers burn out because they've tied their self-worth to shipping the next unicorn feature?

The most innovative teams—whether they're 16 or 46—understand that building something meaningful requires embracing process over outcomes. They celebrate the breakthrough debugging session, the elegant solution to a complex problem, the moment when a struggling team member finally "gets it."

This doesn't mean lowering standards or accepting mediocrity. It means recognizing that sustainable excellence comes from teams that find fulfillment in the work itself, not just external validation.

The Bigger Picture

After 15 years in FIRST and several years in corporate tech, here's what I know: the principles that make great robotics teams aren't confined to competition season. They scale. They transfer. They work.

The high school students I mentor approach problems with curiosity, embrace learning at every level, focus on their own growth, make smart trade-offs, and find pride in the process. Meanwhile, I've watched talented corporate teams struggle because they'd forgotten these fundamentals.

We spend so much time talking about what students learn from industry mentors—project management, professional communication, real-world engineering constraints. All valuable. All important.

But maybe it's time we started paying attention to what flows in the other direction. Maybe the next breakthrough your team needs isn't a new framework or methodology. Maybe it's the fearless curiosity of a sophomore who doesn't know something is supposed to be impossible.

Maybe it's the collaborative spirit of a team where anyone can teach and everyone learns.

Maybe it's the relentless focus on tomorrow's robot instead of yesterday's competition.

Maybe it's time to ask: what would your team accomplish if you approached problems like champions-in-training instead of experts-with-everything-to-lose?

I'm always looking to connect with other FIRST volunteers and corporate engineers who see these connections. What lessons have you learned from unexpected places? Find me on LinkedIn or follow @code_with_kate for more perspectives on where engineering excellence really comes from.